When Signals Lie: Radio Physics and Mobility Insight

Mobility analytics often start with a simple idea: stronger signal means closer user. The real world is not that simple.

Radio waves bend, scatter, reflect, and get absorbed by the materials they encounter. Those physical effects can shift a device's apparent location by tens or hundreds of meters, even when the data pipeline is mathematically correct.

This post is the first in a short series on radio propagation and positioning accuracy. The goal is not to explain every equation, but to show why physics matters and how we validate positioning logic when ground truth is scarce.

The Ground Truth Myth

Everyone asks for ground truth: "Show me exactly where people were."

For population-level insight, that is rarely feasible. Following thousands of individuals with high-precision GPS 24/7 is expensive, intrusive, and often legally impossible.

So instead of waiting for perfect ground truth, we build controlled synthetic worlds. If we can simulate the physics, we can generate known truth and test whether our algorithms behave correctly.

That lets us answer two different questions:

- Validation: Are we building the right product? Do our outputs match real-world behavior?

- Verification: Are we building the product right? Does the algorithm behave consistently under known conditions?

Verification comes first. If a positioning model cannot track a device in a noise-free synthetic world where physics is known, it will not perform in a messy, real-world network.

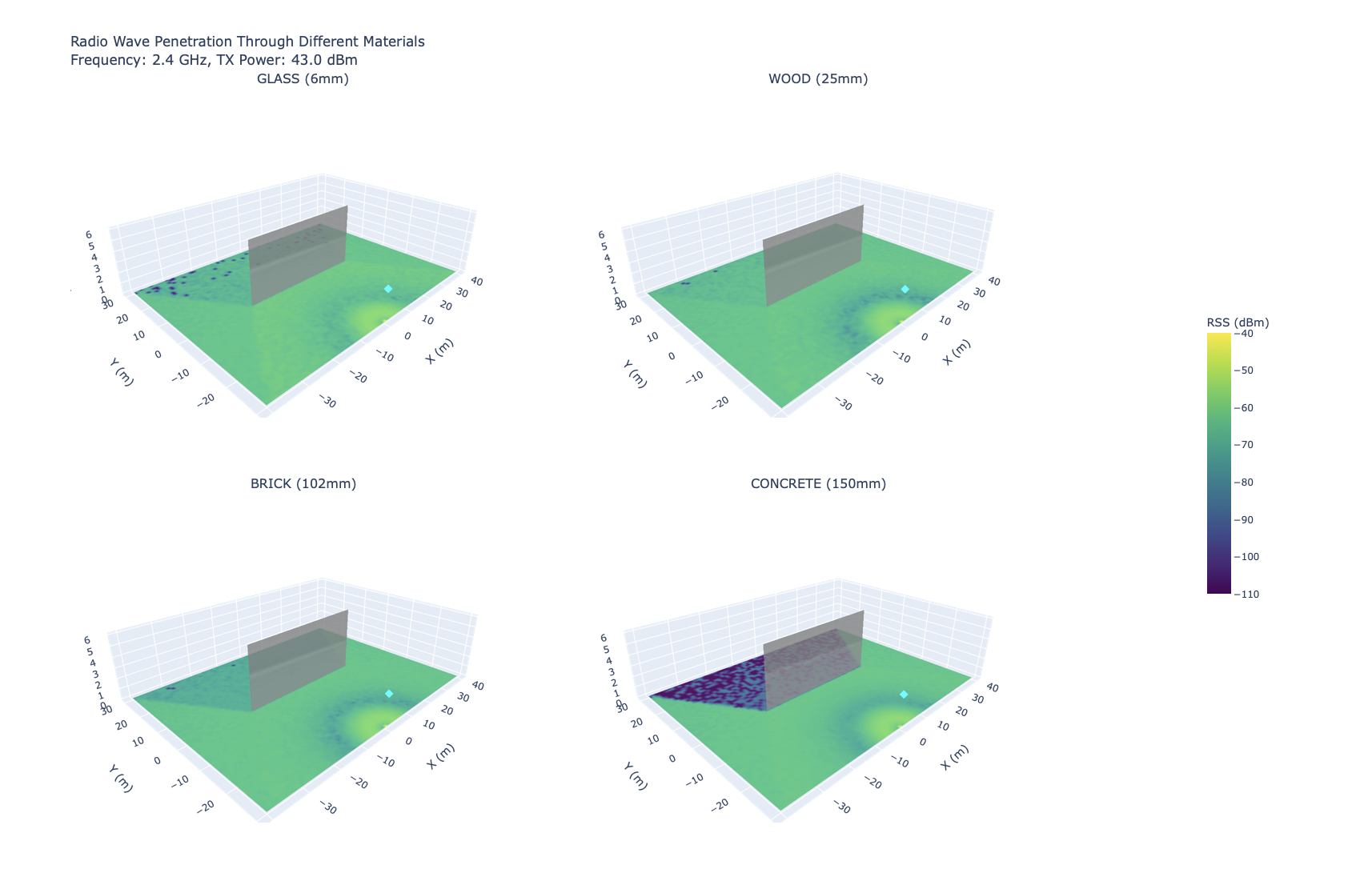

The Wall Problem: Materials Matter

Radio waves are not magic; they are electromagnetic energy that is absorbed or passed through by different materials.

Glass, wood, and concrete all treat the same signal differently. If a device sits behind a concrete wall, the signal may be weak not because the device is far away, but because the wall absorbed most of the energy.

In positioning models, this can create a false distance bias. The model sees "weak signal" and pushes the device outward, when the true issue is attenuation.

The solution is not to guess; it is to model the environment and account for material properties where possible.

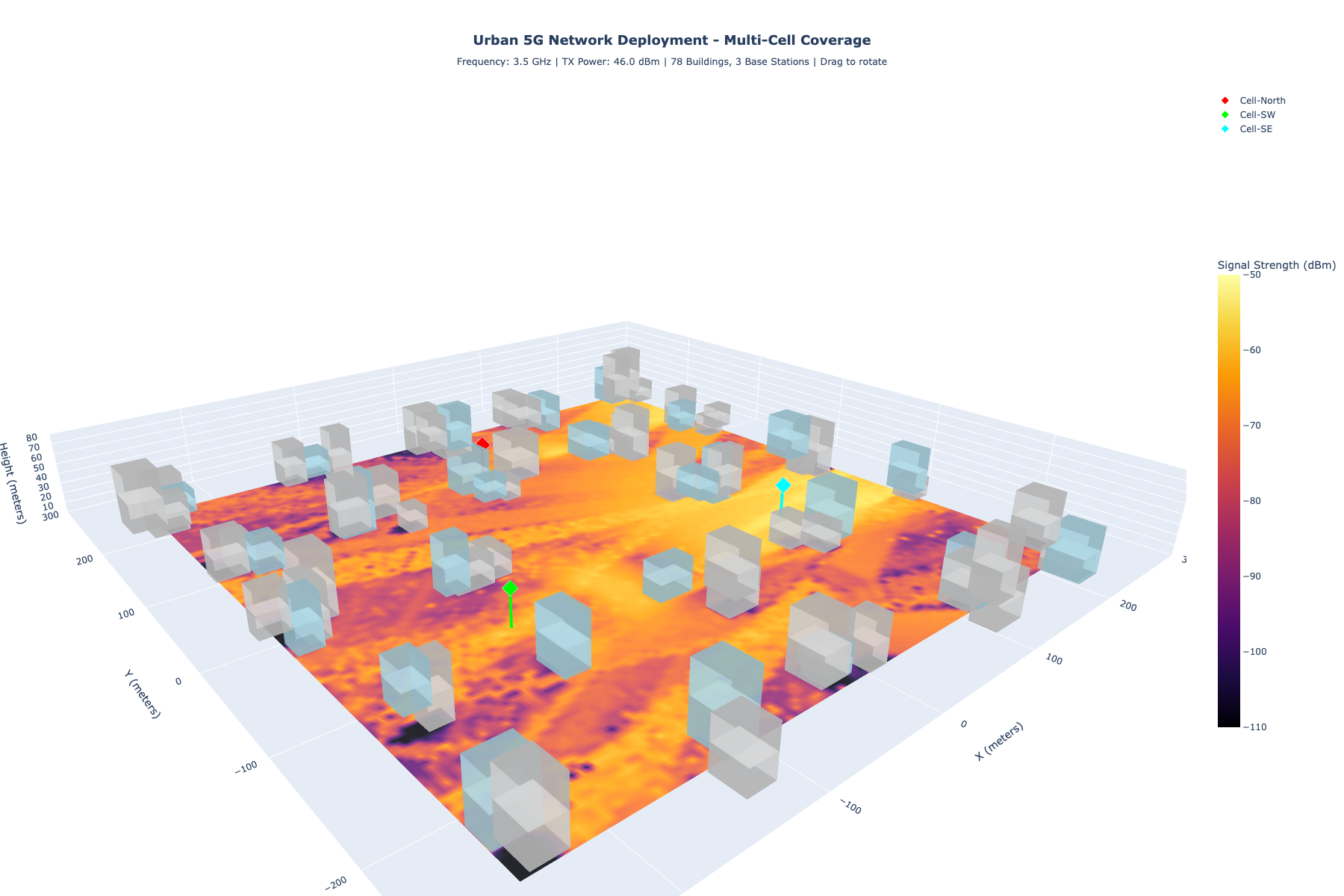

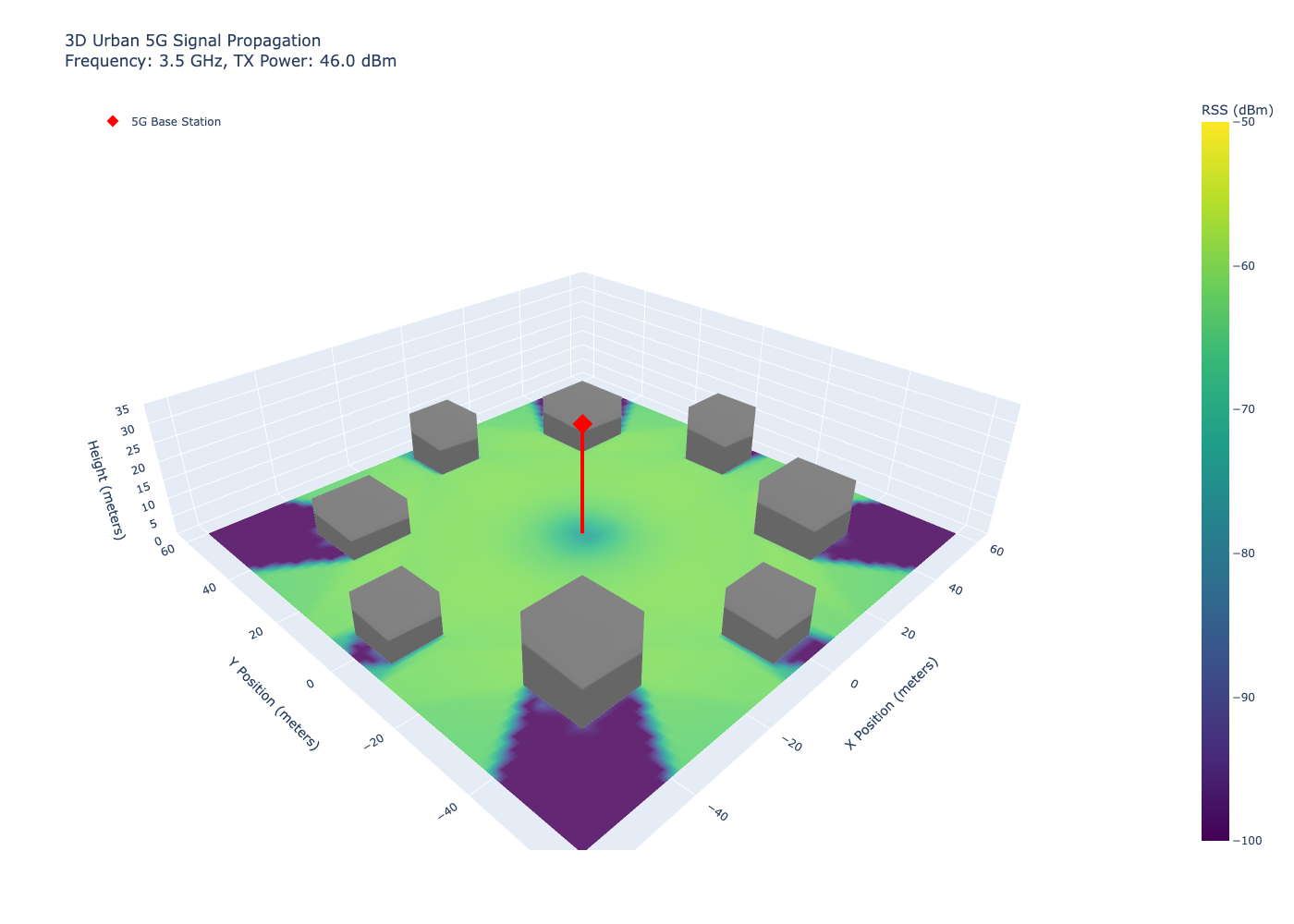

Urban Canyons: Diffraction and Reflections

Cities create complex radio environments. Tall buildings block line-of-sight paths and force waves to travel around obstacles.

In these cases, the strongest signal might not be the direct path at all, but a reflection off another building. This can confuse time-of-arrival and angle-of-arrival models, which assume the shortest path is the strongest one.

The visual below shows how a signal behaves in a simplified urban environment. The apparent “hot spots” are not always where you think they are.

For mobility analytics, this matters because short-term localization errors can ripple into aggregated insights. If the errors are systematic, they can create false movement corridors or invisible activity areas.

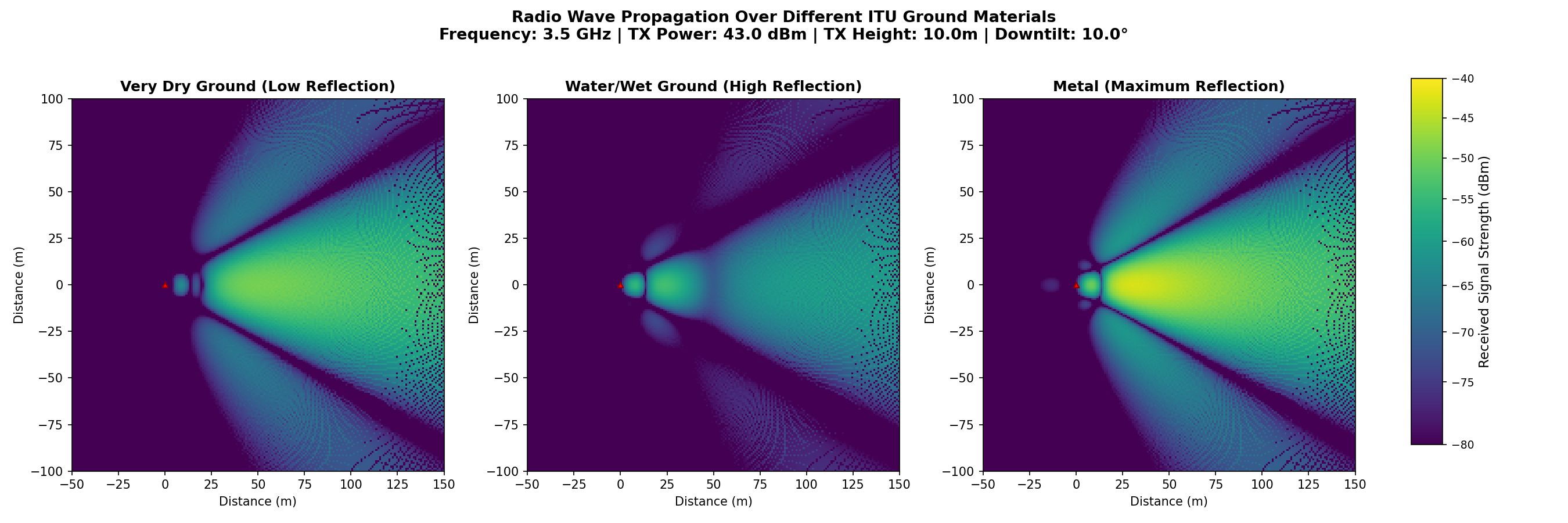

The Nordic Challenge: Water as a Mirror

In coastal cities, radio propagation meets a special surface: water.

At low angles, water behaves like a near-perfect mirror. A direct signal and its reflection can combine in ways that either cancel each other out (dead zones) or amplify each other (false strong signals). This is known as multipath fading.

The chart below compares propagation over land versus water.

Over land, signal strength fades smoothly. Over water, you see interference “ripples” where the reflection and direct path interfere. A user in a cancellation ripple can look far away, even if they are only a short distance from the transmitter.

This is one reason coastal cities and fjord environments can show location errors that seem inconsistent or unstable at first glance.

Why This Matters for Mobility Insight

Mobility analytics are built on aggregates, not individuals. But if the underlying location estimates are biased by physics, the aggregates can inherit those biases.

This is why we invest in propagation-aware verification:

- It helps explain why certain areas appear “empty” in network data.

- It separates true movement changes from signal artifacts.

- It allows us to calibrate positioning logic before deploying it on real-world data.

In short: good mobility insight starts long before the algorithm. It starts with physics.

What’s Next

In the next post, we will move from synthetic validation to field calibration: how we combine propagation modeling with sparse real-world measurements to validate accuracy at scale.

If you are working on urban mobility, radio planning, or trusted statistics, we would love to compare notes.